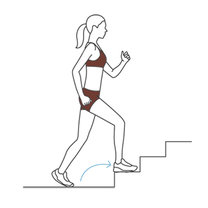

ćwiczenia Na Schodach. Dziewczyna Robi ćwiczenia Na Schodach. Mięśnie Nóg I Pośladków. Izolowany Na Białym Tle Ilustracji - Illustration of motywacja, atleta: 230273008

Bieganie po schodach. Jak to robić poprawnie? Co to daje? | BieganieUskrzydla.pl - bieganie, trening, maraton

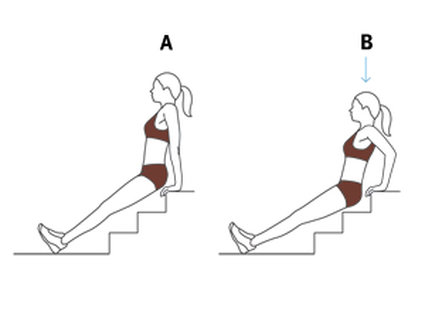

Home excercises (workout) on stairs (gimnastyka domowa dla starych - ćwiczenia na schodach) 50+ - YouTube

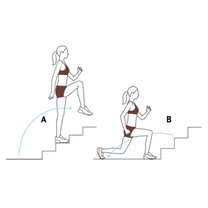

![Ćwiczenia na schodach modelujące pośladki [ZDJĘCIA] - PoradnikZdrowie.pl Ćwiczenia na schodach modelujące pośladki [ZDJĘCIA] - PoradnikZdrowie.pl](https://cdn.galleries.smcloud.net/t/galleries/gf-obiq-9GsW-CbKk_przysiad-z-odwodzeniem-nogi-w-tyl-664x442-nocrop.jpg)

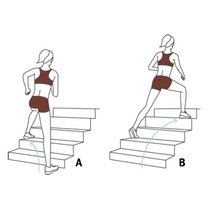

![Ćwiczenia na schodach modelujące pośladki [ZDJĘCIA] - PoradnikZdrowie.pl Ćwiczenia na schodach modelujące pośladki [ZDJĘCIA] - PoradnikZdrowie.pl](https://cdn.galleries.smcloud.net/t/galleries/gf-J7Mz-WhkC-a7eV_cwierc-przysiad-1920x1080-nocrop.jpg)