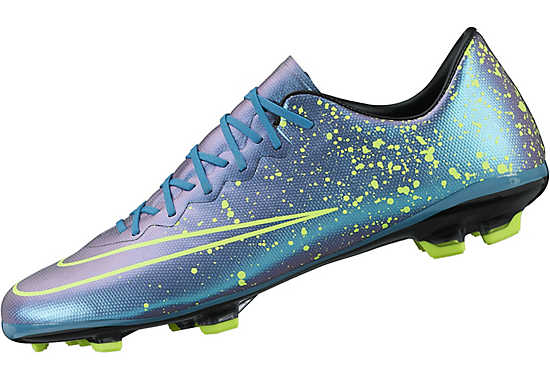

Nike Mercurial Vapor X FG CR7 Savage Beauty - Black / Total Crimson / Metallic Silver / White - Football Shirt Culture - Latest Football Kit News and More

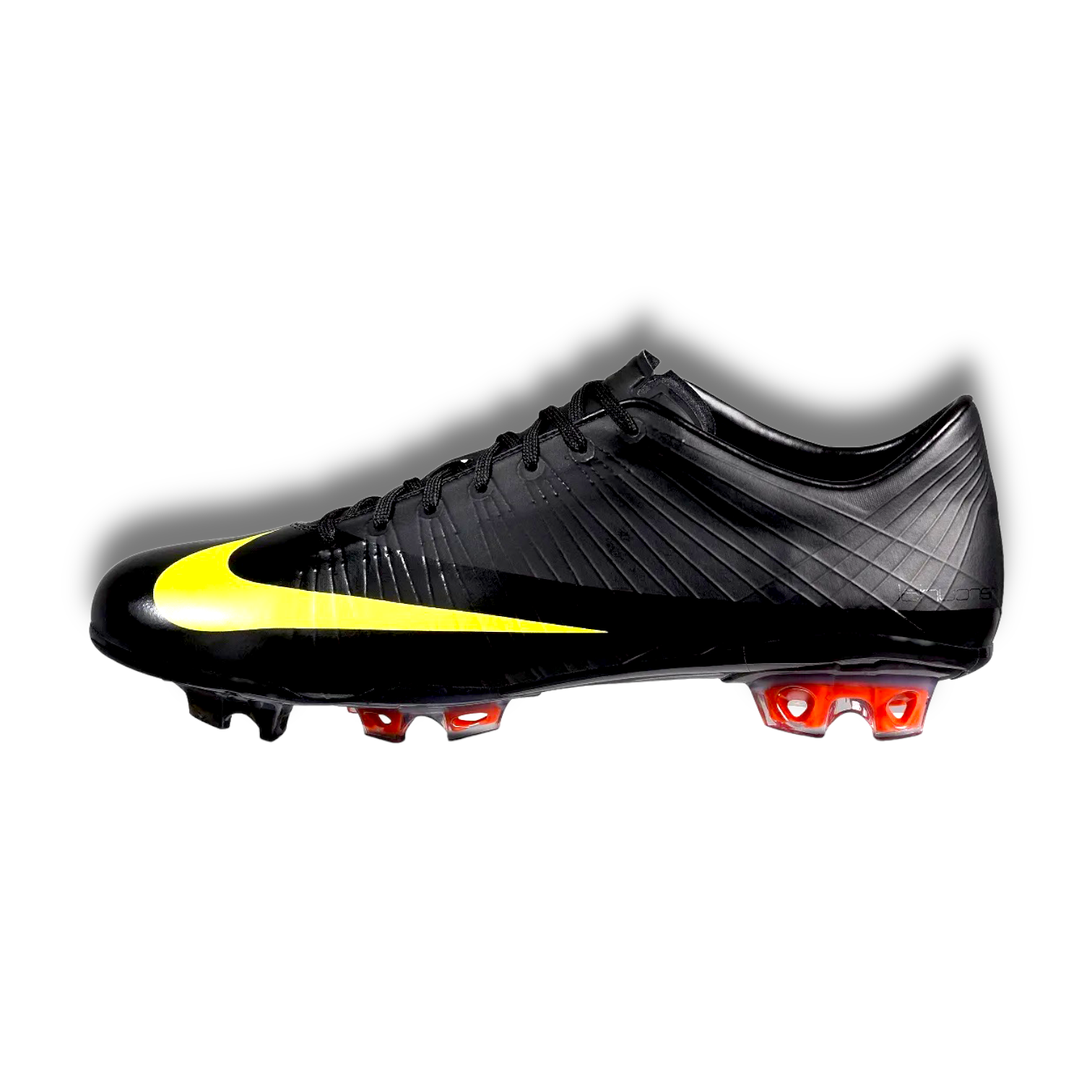

Nike Soccer Shoes - Nike Mercurial Vapor X FG - Firm Ground - Soccer Cleats - Black-Black-Hyper Punch-White | Pro:Direct Soccer

![Nike Mercurial Vapor X Leather Firm Ground [BLACK/HYPER PINK/BLACK] (9.5) - Walmart.com Nike Mercurial Vapor X Leather Firm Ground [BLACK/HYPER PINK/BLACK] (9.5) - Walmart.com](https://i5.walmartimages.com/seo/Nike-Mercurial-Vapor-X-Leather-Firm-Ground-BLACK-HYPER-PINK-BLACK-9-5_6b82b905-8b8b-4f53-86b2-9587a6da80b7.95228da3257c293db3b09b4cb266142b.jpeg?odnHeight=768&odnWidth=768&odnBg=FFFFFF)