T5 Lámpa, Cső, Fali Lámpa, Led Fénycső Cső, Fali Lámpák 220v Fürdőszoba Világítás öltözködés Lámpa Tükör Könnyű Alumínium Lámpatestek ~ LED Lámpák \ Kedvezmeny-Bolt.cam

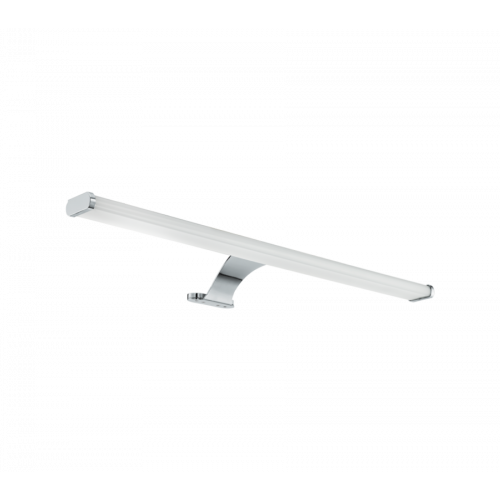

LED lámpatest , tükörvilágítás , 7.4 Watt , 40 cm , természetes fehér , króm , IP44 , EGLO , PANDELLA , 96064

LED lámpatest , tükörvilágítás , 10 Watt , 60 cm , meleg fehér , króm , IP44 , EGLO , VINCHIO , 98502

Vásárlás Modern vízálló fali lámpa tükör lámpa teleszkópos tartó arany fali lámpa fürdőszobai világítás étterem világítás led lámpatest \ Led lámpák - Latest-Supermarket.cam

Rendelés 9w/12w/14w/16w/20w led tükör előtt fény actylic fali gyertyatartó lámpa, lámpa smd 2835 zuhanyzó, mosdó fehér/fekete kagyló ~ Led Lámpák / Timooo.co

A Modern Led Hosszú Tükör Fény Akril Fali Lámpa Fürdőszobai, Világítás Lámpatest, Beltéri Vízálló, Wc, Rozsdamentes Acél Gomb Kapcsoló kedvezmény / Led lámpák | Elemeket-Gyar.today

Tükrös, fénycsöves lámpák, armatúrák | Lámpa, csillár, világítás - Fénypost Webáruház - lámpák és csillárok

V-TAC Fürdőszoba tükör világítás: Fine fali LED lámpa, króm végdísszel (10W) hideg fehér - Ár: 7 990 Ft - ANRO

Rábalux Albina 1448 tükör világítás matt fehér fém LED 8 450 lm 4000 K IP23 G - Képmegvilágító lámpa - Navalla lámpa webáruház, világítástechnika

Fali Lámpa Lámpatest Led Fürdőszoba Lámpák Felett Tükör, Lámpa, Modern Rozsdamentes Acél Gyertyatartó Fali Lámpák Fürdő Smink Hiúság Világítás Kiárusítás < Led Lámpák | Mprice.shop

V-TAC Fürdőszoba tükör világítás: Fine fali LED lámpa, fehér végdísszel (10W) természetes fehér - Ár: 7 990 Ft - ANRO