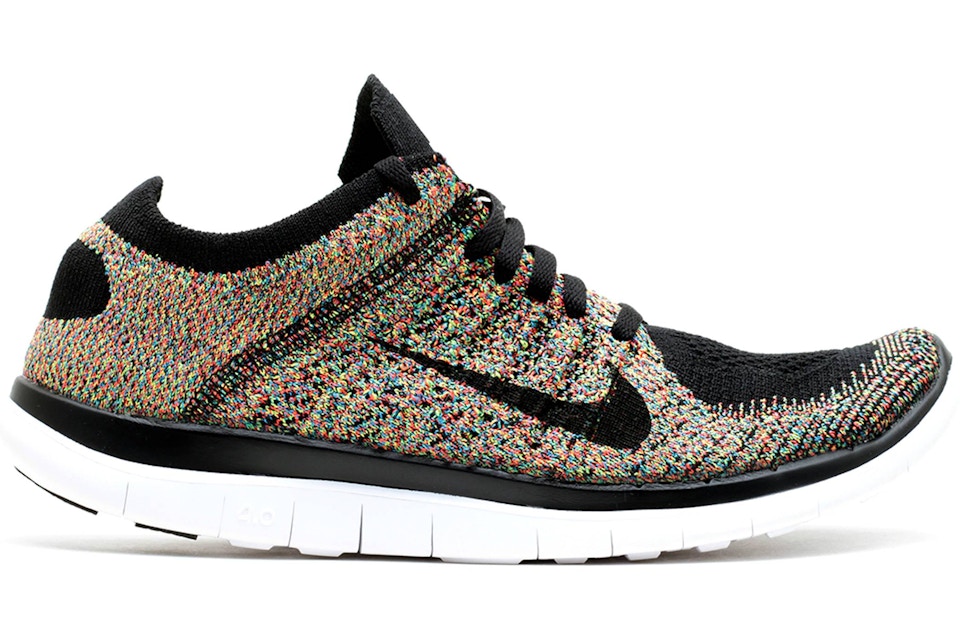

Nike 'Free 4.0 V2' Running Shoe | 14 Pairs of Running Shoes to Beat the Winter Blues | POPSUGAR Fitness Photo 9

nike free 4.0 flyknit blue,Nike Free 4.0 Flyknit 2015 - Women's - Running - Shoes - Racer Blue/University Blue/Hyper Orange/Bla

nike free 4.0 flyknit running shoes,Nike Free RN Flyknit 2017-Men's-Running-Shoes-Deep Royal Blue/Black/Persian Violet-sku:8084

nike free 4.0 flyknit shoes,Nike Free RN Flyknit 2017-Men's-Running-Shoes-White/Black/Stealth/Pure Platinum-sku:80843101

nike free 4.0 flyknit pink,Nike Free 4.0 Flyknit 2015 - Women's - Running - Shoes - Pink Foil/Black/Sunset Glow-sku:17076600