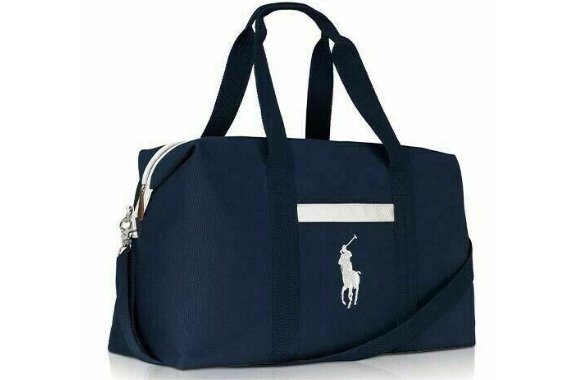

توییتر \ theperfumeshop در توییتر: "FREE GIFT with purchase! Discover our fantastic Ralph Lauren range and get a complimentary Polo Ralph Lauren bag. Shop now https://t.co/KFU3o5kU9a Subject to availability. T&Cs apply

The Perfume Shop - FREE GIFT with purchase! Discover our fantastic Ralph Lauren range and get a complimentary Polo Ralph Lauren bag. Shop now http://ow.ly/eBpI50A3HlU Subject to availability. T&Cs apply

Ralph Lauren Receive a Free Duffel Bag with any large spray purchase from the Ralph Lauren Men's Polo fragrance collection & Reviews - Cologne - Beauty - Macy's

BEAUTY BY SHOPPERS DRUG MART CANADA GWP: Shop Ralph Lauren Polo Fragrance, Receive Free Duffle Bag | 2021 Canadian Gift with Purchase Offer

Ralph Lauren Receive a Free Duffel Bag with any large spray purchase from the Ralph Lauren Men's Polo fragrance collection & Reviews - Cologne - Beauty - Macy's

SHOPPERS DRUG MART CANADA GWP: Shop Ralph Lauren Romance EDP & Receive Free Teddy Bear | In-store; Valentine's Day 2021, Canadian Deals & Gift with Purchase Offer

Ralph Lauren Gift with purchase of any two Ralph Lauren Fragrance men's fragrance products! | Bloomingdale's

Ralph Lauren Receive a Free Teddy Bear with any large spray purchase from the Ralph Lauren Romance Fragrance Collection & Reviews - Perfume - Beauty - Macy's

Ralph Lauren Receive a Free Polo Bear with any $90 large, jumbo, or gift set purchase from the Ralph Lauren Polo Men's Collection & Reviews - Perfume - Beauty - Macy's