Lampa-shop.hu - www.lampa-shop.hu💡 #bevilágítjukotthonát #belterivilagitas #lakberendezés #lakásdekor #otthondesign #interiordesign #homeinspiration #modernlámpa #designlampa #lampa #home #homedesign #rendeljonline #followme #love | Facebook

Vásárlás Kreatív Szőlő Csillár Villa Lépcső Plafonról Lógó Csillár Világítás Hotel Medál Lámpa Duplex Lakás Art Dekor Világítás > Mennyezeti Lámpák & Rajongók / Depot-Rialto.cam

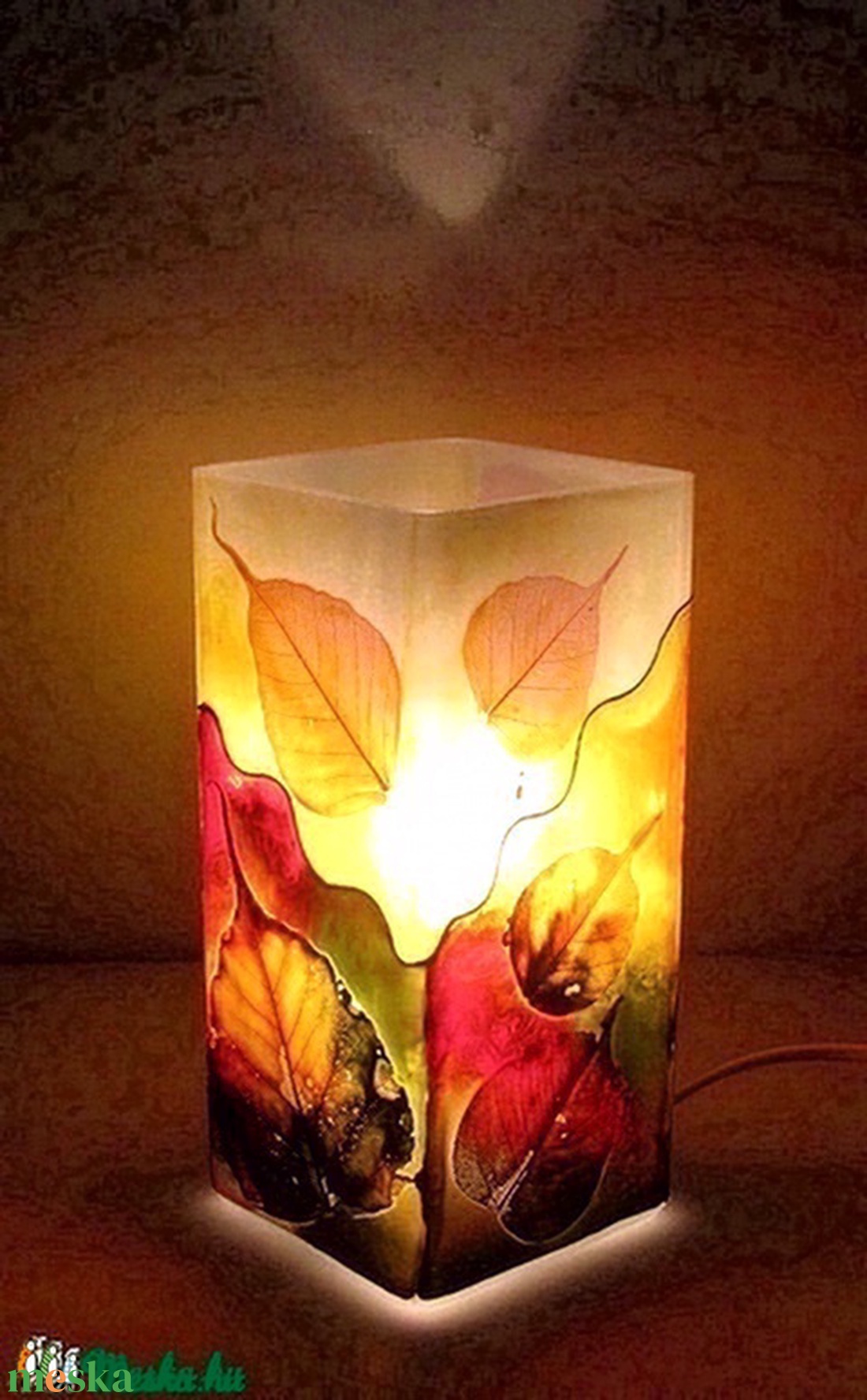

Világítás kisokos: lakás, ház belső tereinek megvilágítása - 2. rész, nappali, hálószoba, gyerekszoba - Lakberendezés trendMagazin

Lakberendezési 4 Kis Macska Alatt Egy Utcai Lámpa, DIY Fali Matrica Háttérkép Art Dekor Freskó Szoba Matrica Adesivo De Parede Matricák Kategóriában. Lakberendezés

Vásárlás 3d éjjeli lámpa fa mulan mushu cirip éjjeli gyerekeknek baba-szoba dekor fény usb elemes este lámpa 3d-s illúzió \ Led lámpák ~ Szallitas-Koltsegvetes.cyou

Rendelés 3d Éjjeli Lámpa Kirara Ábra a Szoba Dekor LED színváltó Éjjeli Anime Ajándék Gyerekeknek Hálószoba Dekoráció 3d Lámpa Inuyasha - LED Lámpák ~ Tetejere-Nagykereskedelem.today

Rendelés 3d Éjjeli Lámpa Kirara Ábra a Szoba Dekor LED színváltó Éjjeli Anime Ajándék Gyerekeknek Hálószoba Dekoráció 3d Lámpa Inuyasha - LED Lámpák ~ Tetejere-Nagykereskedelem.today

Forró Eladó Fényűző, Modern Rövid Divat K9 Kristály Led E27 állólámpa Nappali Szoba Dekor Lámpa Lámpák And árnyalatok - Fashionprices.news

Price history & Review on Corner Floor Lamps RGB Bedroom Living Room Decor Lighting Standing Lamp UK Plug | AliExpress Seller - High Quality Decor Store | Alitools.io