Blumfeldt Vermont, bílé, zahradní křeslo, zahradní židle, adirondack, 73 x 88 x 94 cm, sklopitelné (GDMB2-Vermont-White) od 2 639 Kč - Heureka.cz

Venkovní Nábytek Houpací Křeslo Dřevěné 4 Barvy Americké Country Styl Starožitné Vintage, Dospělý, Křeslo Velké Zahradní Houpací Křeslo Tato Kategorie. Zahradní židle. Newshopper.news

Unikátní křeslo H-221 navrženo Jindřichem Halabalou ve třicátých letech pro Uměleckoprůmyslové Závody v Brně | Nanovo

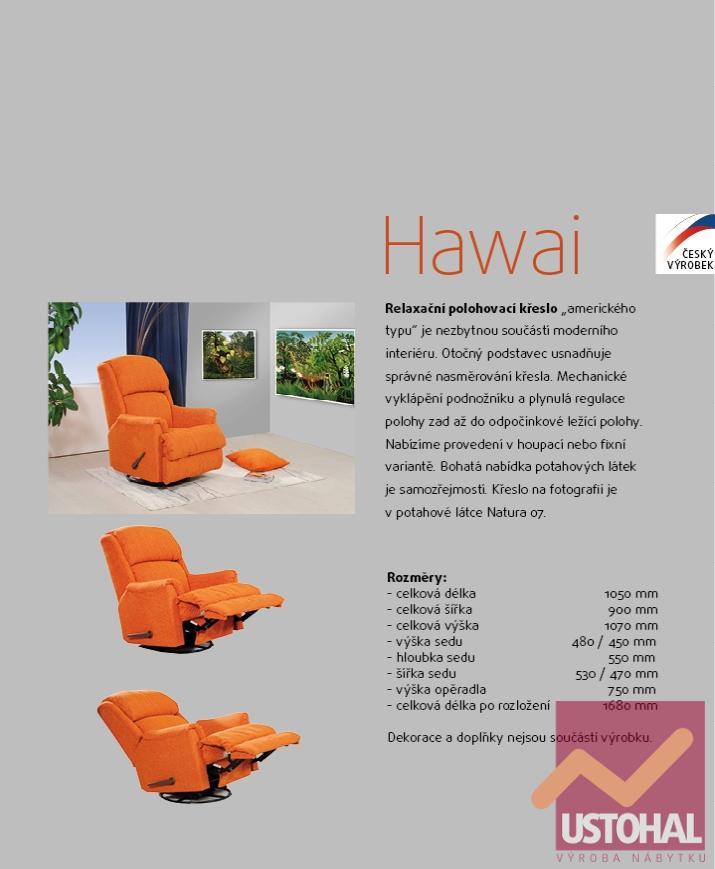

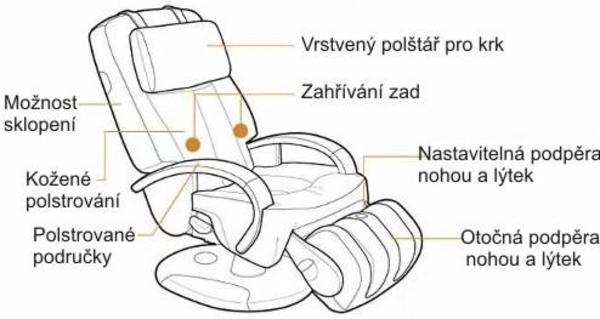

Masážní Křesla Praha - Americké masážní křeslo je vhodné do každého interiéru a jako jediné jde napolohovat jako lůžko. Vhodný dárek pod stromeček. Křeslo je vyhřívací . Masáž Strech se postará o